Less Than Nine Lives to Live: A grandfather's aviation pursuits and adventures temp fate

Cheating Death in the Canadian Wilderness and Spectacular Plane Crash

Prior to my grandfather’s pre-commercial flight record attempts and successes during the early 1930s, he had already experienced near misses, enemy fire, and undoubtably mechanical failures while flying for the French in Escadrille Breguet 111 during World War I during 1918.

As experience was the most valuable teacher in early aviation, James G. Hall and many other pilots from the Golden Age of flight would have benefited from frontline action in World War I. Taking to the air again, during the late 1920s, and more specifically 1930 to 1932, my grandfather and other flyers would be challenging the elements of weather, plane malfunctions, and simply “pushing their luck” as they competed for ever faster flight route times across the U.S., Canada, and Mexico.

Captain Frank Hawks, the greatest record-breaking pioneer of pre-commercial flight, both at home and abroad, would run out of luck. This happened on September 5, 1938, as he was touring the U.S. promoting and flying demonstrations in a newly built “safety” aircraft, the Gwinn Aircar. He had also just become Vice President and Production manager of the Gwinn Aircar Company. Time magazine reported on the incident with an eyewitness account:

“Last week, Frank Hawks shuttled to East Aurora, N.Y. to show off his polliwog [new test airplane] to a prospector, Sportsman J. Hazard Campbell. He landed neatly on the polo field in a nearby estate at about 5pm climbed out, chatted awhile with prospector Campbell and a cluster of friends. Presently he and Campbell took off smartly, cleared a fence, went atilt between two tall trees, and passed from sight. Then there was a rending crash, a smear of flame, silence. Covering half a mile, a fearful group raced from the polo field. From the crackling wreck they pulled Frank Hawks; and from beneath a burning wing, prospector Campbell – both fatally hurt and died before reaching a hospital. The ship that could not stub its toe had tripped on overhead telephone wires.”

Hawks had announced his retirement from air racing back in 1937 and then joined Gwinn Aircar Company. Around that time, he had told friends, “I expect to die in an airplane.” My grandfather and other pilots of the period would certainly have taken this loss hard – personally, professionally, and psychologically. Undoubtedly, my grandfather had come to know and respect Hawks as an unrelenting competitor, a fellow adventurer in the sky, and a legendary aviator who had advanced the technology and records of flight.

James G. Hall would use up several of his proverbial “nine lives” as well. As they were the “astronauts” of their generation in flight, pushing route distances and speed boundaries, each pilot understood the inherent dangers. However, beyond their control, even as Captain Frank Hawk’s fate attests, was that indiscriminate moment of bad luck. It was not discernible like skilled piloting or navigational expertise, which could get you out of trouble, saving you from an amateur’s mistake. But instead, an element of fatal surprise – out there, in front of you, past the horizon of your next glance.

As my grandfather started his post-World War I flying interests in the late 1920s, he had also become a successful and ambitious stockbroker, purchasing a seat and membership on the NYSE at the age of 31. Prior to this significant achievement of membership to the most prestigious and selective of financial guilds, my grandfather had started his Wall Street career with the brokerage firm of Samuel Ungerleider & Company, one of the original firms to join the NYSE back in 1920.

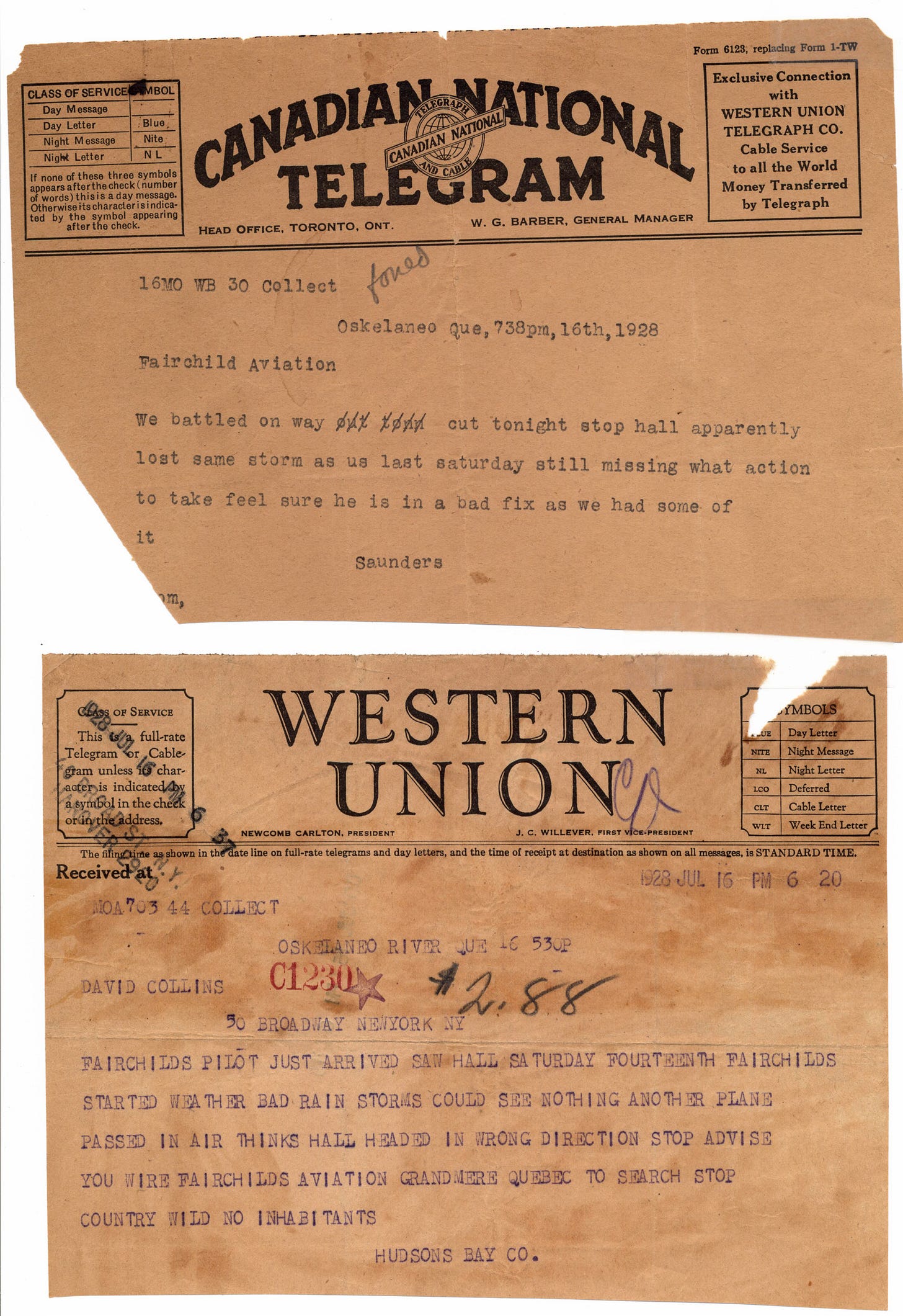

It appears that my grandfather, then a member of the brokerage firm Samuel Ungerleider & Company, along with fellow broker Enos Curtain of Jackson & Curtin, were finding adventurous pursuits outside of their Manhattan Wall Street addresses in downtown New York City. With my grandfather piloting, both young brokers had taken-off in flight, from the East River in New York City on July 7, 1928 “in a Stearman seaplane with Hall at the controls.” Their destination was the tiny town of Oskelanco, in Northern Quebec, Canada.

The objective of this bold journey was, according to numerous newspaper reports that covered this occurrence, to “inspect some mining properties related to gold” for Ungerleider’s Wall Street brokerage. After making their mining inspection, and then upon departure from Oskelanco, they were seen by another pilot, as described in the Pittsburgh Gazette:

“Hall, at the controls, reached Oskelanco, a Hudson Bay Company outpost and left Tuesday after inspecting some gold mining properties. That day their plane, or what was believed to be their plane, was sighted by another aviator, who reported he saw it during a storm flying in a direction away from New York and away from civilization.”

Both men were expected back in New York and scheduled to attend a party at Ungerleider’s home in New Jersey the following evening. When they failed to attend the party that evening, and there being no way of communicating with them, immediate concern and action was taken by fellow broker and friend David Collins. A series of connections would follow that started a manhunt of 16 search planes. As related by the following article in the Pittsburgh Gazette, this string of communications that occurred reveals a tight inner circle of financial, corporate, and government connections in my grandfather’s orbit of social and business contacts. These relationships and timely actions, taken on his behalf, would probably save his life:

“David Collins, a partner of the firm (Ungerleider & Co.), instituted an inquiry. L.F. Loree, president of the Delaware & Hudson railroad, Collin’s father-in-law, asked F. Trubee Davison, Assistant Secretary of the War in charge of aviation, to request aid from the Canadian government. The Fairchild Aviation Corporation field at Grandmere, Quebec, sent out six planes and 10 more were ordered out from Paper Mill, near Grandmere.”

On July 17th, 10 days after their disappearance into the wilderness of Northern Quebec, they were “found” according to nationwide newspaper headlines following the incident. In actuality, my grandfather and his two associates had escaped certain fate by being resourceful and managing to survive and self-rescue in a very inhospitable Canadian mountain environment, “using just about every form of transportation: walking, flying, canoeing, and climbing mountains.”

A sudden major localized rainstorm had brought James G. Hall’s seaplane down 150 miles north of Oskelanco in Quebec, Canada – with a forced landing into a vast high mountain wilderness. Without any hope of rescue or being located, my grandfather, fellow broker Enos Curtin, and intended return passenger R. T. Gilman of Montreal, had walked through the Canadian wilderness for several days. The media had termed this area as being “50 miles from nowhere.” Initially hiking to the top of a local mountain, the men located a ranger station in the distance. Living on canned soup and rigging a fishing pole to catch lake fish, they hiked for 12 hours to reach the ranger station.

Their passenger Gilman gave the Cleveland Plain Dealer newspaper a first-hand account of the ordeal:

Flying into a heavy storm, with about 15 minutes left of gasoline, we landed on Moose Lake – but did not know where we were at the time… finally by hiking up a mountain we could make out a ranger station about 20 miles away. We worked our way to that tower, swimming rivers, wading through marshes, driving through dense bush, struggling along as best we could. We started out at 6 o’clock one morning and reached the ranger station at 5 the next morning. When we got to the ranger’s station – we were saved. He [the ranger] had food to offer us and loaned us a canoe by which we got back to Oskelanco.

The article went on to explain that from Oskelanco, my grandfather was able to secure a plane with additional gasoline, then fly back to his plane at Moose Lake, refuel, and fly back to New York. The outcome of this predicament, under these circumstances, was like being plucked from fate

A much more sensational incident was to occur later during his pre-commercial flight record-making years, in the autumn of 1931. While also having become an established and successful broker on Wall Street, with a seat on the NYSE and a partnership in Collins, Hall & Peckham, and still competing for flight records, James G. Hall was also expanding his aviation contacts and business network.

One such business connection was to occur on the morning of September 21, 1931, as my grandfather was scheduled to fly his Lockheed Altair from Floyd Bennett Airport, Brooklyn, New York, accompanied by Peter J. Brady, president of the Federation Bank, New York and Deputy Commissioner of Docks in Charge of Aviation. Their destination was the American Legion Convention in Detroit where Brady was scheduled to lecture on the subject of labor. The details of the forthcoming accident or “crash,” as it was commonly referred to, were carried in all national and local newspapers across the country – becoming headline news:

“As the plane (piloted by James Goodwin Hall), a bright yellow craft, which has won many speed events, swung over Staten Island, it appeared to falter, then dove into the house below. As the craft struck the house, the gasoline exploded. The plane and the roof both started burning. Brady and the woman in the yard of her home at the time, were both dead when rescuers arrived.”

An additional headline accompanied this newspaper report, from the United Press in New York. His obituary had already been written that afternoon and unofficially published. This was as close a call with destiny as probably any dogfight in the skies over France in combat with German Fokkers during World War I. He walked away with only minor injurie:.

“James Goodwin Hall, noted aviator and holder of several speed records was probably fatally injured when his Lockheed plane crashed into a house in West Brighton, Staten Island, today.”

The following headline, “He Waved Goodbye,” (one of many to be published nationally) appeared the next day, detailing my grandfathers near escape. In this newspaper publication, James G. Hall is pictured in the cockpit of his Lockheed Altair with labor leader Peter J. Brady behind him in the second cockpit, both waving to the press with smiles on their faces just moments before takeoff:

“He waved goodbye – and only minutes later Peter J. Brady, right, labor leader, banker, and chairman of Mayor Walker’s committee on aviation, was killed when the plane in which he was flying to the American Legion convention fell apart and crashed into a bungalow on Staten Island, N.Y. The pilot James Goodwin Hall, leaped in a parachute and escaped death. The picture was snapped just before they took off from New York in Hall’s speed-plane used for establishing records in the sky. The burning plane ignited two houses and 60-year-old Mrs. Mary Trittre, who was sitting in a garden, was burned to death by a shower of flaming gasoline.”

My first recollection of this incident was from my father, Howard Earle Coffin Hall, who was very guarded about his family history. However, I recall a general conversation about James Goodwin Hall’s aviation records, whereby my father had added “he’d crashed off Staten Island, New York and bounced off a roof and into a hedgerow, but otherwise escaped serious injury.”

Fortunately, due to digitized archival newspapers, The Boston Globe’s account dated Tuesday September 22, 1931, contained a personal statement by my grandfather, recalling in detail his recollection of the “crash.” He had rushed to the scene as soon as he had recovered from his perilous descent, and described the accident as follows:

“Fifteen minutes before the crash, my wings began to tremble violently. We were going through dense fog. I noticed we were dangerously close to the ground and I pulled on the stick to gain altitude. The plane failed to respond. We were about 200 feet from the ground when I realized a crash was inevitable. I shouted to Brady to jump, and then I went over the side.” Several eyewitnesses told officials the plane appeared to explode and disintegrate about 100 feet from the ground. After asserting Brady had agreed to take-off in the face of unfavorable weather over the bay, Hall declared: “I have no words with which to express the deep regret and sorrow that I feel over this dreadful accident.”

The “crash” was investigated by the Civil Aeronautics Administration and by local police and no charges were filed. James G. Hall would attend Mr. Brady’s funeral which drew over 1,500 mourners due to his prominent position as a businessman and political figure. Brady’s pall bearers were chosen from the New York State elite, according to local newspaper sources.

My grandfather bought a new airplane, another Lockheed Altair, just a couple of weeks after his accident. Certainly the tragic loss of life under his piloting during this incident would remain in his memory forever. But this was a different period of history, marked by large scale loss of life.

The outbreak of the Spanish Flu from January 1918 to December 1920 killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide, and there were an estimated 20 million deaths during World War I, just 13 years earlier. Also, from my grandfather’s perspective, there were the regular occurrences of accidents, injuries, and deaths that were unavoidable in the pre-commercial flight competitions he was participating in during this early period of commercial flight.

To return to the pursuit of flight records so quickly after such an accident, including two fatalities, was not a cold or flippant disregard for grief regarding the loss of life from this spectacular and horrendous “crash” that day on September 21, 1931. Instead, it was more in keeping with an acceptance of personal risk taking and a time in our history when exploration and adventure carried greater danger and consequences. During the days of experimental flight in the early 1930s, anyone getting into a 2–seater private plane – pilot or passenger – was accepting a moderate degree of risk.

My grandfather’s adventurous flying exploits and record setting attempts against his then main rival Captain Frank Hawks, would now combine by joining and becoming a public figure in the Anti-Prohibition campaign that was gaining momentum. He became an active member of the “Crusaders,” whose organizational mission was to repeal the 18th Amendment, which had banned the manufacture, sale, and transport of alcoholic beverages in 1919. James G. Hall would use his new plane as a flying advertisement, complete with decal slogans spread across the fuselage. As this was a contentious political issue heading into the presidential election of 1932, my grandfather would receive an abundance of newspaper coverage. Stay tuned for the next chapter in my grandfather’s adventourous life.